Handling chivalry in RPGs is hard. Genre fiction loves chivalry and honor almost as much as it loves jaded pessimism – and it often shoves the two philosophies together in ways that seem to clash. The classic example is the paladin and the rogue. How’s a GM supposed to have both in the same party without one of them (usually the paladin) looking like a moron? A real-life incident from 1351 may help shed some light on how to walk this tightrope.

The Hundred Years’ War between England and France (1337-1453) was a famously awful mess. Millions died, countless towns were burned (sometimes multiple times), and the whole affair settled remarkably little. Yet the leadership of both sides were ostensibly bound by the laws of chivalry, which theoretically ought to have limited the violence. It’s a great example of how honorable combat usually doesn’t hold up in the real world. Yet amid the blood and the grime, there was a bright spot: the Combat of the Thirty, an example of chivalry held up for centuries to come.

In 1351, an English castellan (lord of a castle) in Brittany was riding past a fortress occupied by Breton forces fighting for France. When he saw that no one inside the castle was going to come out and fight, the Englishman called up to the Bretons on the ramparts to ask if there was anyone inside who might want to joust with him “for the love of their ladies”. The joust he was proposing was no tournament game, but a deadly bout with steel-tipped lances!

The Bretons politely declined, but offered a counterproposal. “We will choose twenty or thirty of our companions in the garrison and we will go to an open field, and there we will fight as long as we can endure it; and let God give the victory to the better of us.” The two sides agreed on a date and time, then parted.

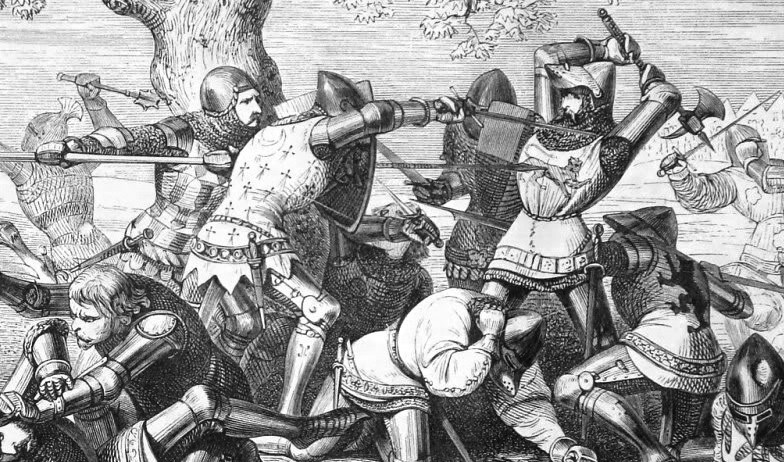

The day of the combat, both sides arrived with thirty men-at-arms. The fighters didn’t pair off or anything: it was just a giant scrum of two teams of thirty men trying to kill each other. They fought mounted and afoot, with swords, daggers, spears, and axes. The fighting lasted for hours. Over a dozen people died. The French side ultimately won, but literally all the combatants who survived were badly wounded.

The outcome had no impact on the broader course of the war. Indeed, it wasn’t intended to. This was sixty guys getting together to beat the stuffing out of each other for no other reason than the joy of combat and the glory they would earn for living up to a chivalric ideal.

And glory they did earn! In the context of the era, what these sixty combatants did was the pinnacle of chivalric achievement, made grander still by the backdrop of an incredibly un-chivalric war. More than twenty years later, a French historian recorded that one of the combatants still held a place of unique honor at the court of King Charles V specifically because of the knight’s participation in the Combat of the Thirty. Ironically, though King Charles may have valued chivalry highly, his successes in the Hundred Years’ War were arguably due to his unchivalrous pragmatism.

The central takeaway from the Combat of the Thirty is this: your campaign doesn’t have to be tonally consistent to be believable. Even in the midst of a hideously unchivalrous period in Western history, chivalrous acts still occurred. At your table, you can have your Jedi behave honorably and your bounty hunter be ruthlessly pragmatic and give both a decent shot at success.

The most fun campaigns support a diversity of PC worldviews. If you’re playing Song of Ice and Fire Roleplay, you can have an idealistic Brienne-type PC and a nihilistic Sandor Clegane-type PC in the same party without ever determining which one of them is ‘right’ about how the world works. Indeed, it’s more fun if you don’t. A campaign with a single underlying philosophy strikes only a single note. A campaign that strikes many notes doesn’t get old as quickly – and it has a little more tension too.

The Combat of the Thirty shows us that a campaign with only a single worldview isn’t realistic. And experience shows us it’s less fun.

For more RPG content grounded in real-world history and folklore, head over to the Molten Sulfur Blog, where Tristan publishes adventure hooks, adventure sites, and NPCs every Tuesday.

All quotes are from the Chroniques of the 14th-century historian Jean Froissart.